Off-label drug use in Psychiatry Outpatient Department: A prospective study at a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital

- *Corresponding Author:

Abstract

Introduction: Off-label drug prescribing is very common in Psychiatry.US-Food and Drug Administration has defined off-label drug as “use of drugs for the indication, dosage form, regimen, patient or other use constraint not mentioned in the approved labeling.” Objective: The objective was to evaluate off-label drug use in patients attending Outpatient Department of Psychiatry. Materials and Methods: One year prospective, cross sectional study was conducted on patients attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department. Demographic data, clinical history, and complete prescription were noted in the predesigned proforma and prescriptions were analyzed for off-label drug use as per British National Formulary-2011. Result: A total of 250 patients were enrolled with mean age 40.36 ± 12.3 years. Most common diagnosis was major depressive disorder 101 (40.4%). A total of 980 drugs (mean 3.68 ± 1.42) were prescribed out of which 387 (39.5%) were off-label. Of 250 patients, 198 (79.2%) received at least one off-label drug. Psychopharmacological agents most frequently used in off-label manner were clonazepam 31 (12.4%), lorazepam 30 (12%), and trihexyphenidyl HCl 25 (10%). Prevalence of off-label use of these three drugs was significantly higher than other off-label drugs (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001 respectively). Inappropriate indication was the most common category of off-label use. There was positive and significant correlation between off-label prescribing and number of drugs (r = 0.722, P ≤ 0.000). Off-label prescribing was statistically significantly higher in 21–40 year age group, but no difference was seen in any co-morbid condition or in between any psychiatric disorder. Conclusion: Off-label drugs use is common in psychiatric OPD in our setup. Clonazepam, lorazepam, and trihexyphenidyl HCl were the most frequently used drugs in off-label manner.

Keywords

Drug utilization, off-label, psychiatry, psychopharmacological agents, rational drug use

Introduction

Marketed medications have to be safe and effective for their intended use. Any such use of drug products is submitted to rigorous scrutiny before marketing approval inform of in vitro studies, animal studies, clinical trials. These data provide specific labeling information, that is, approved indications for use, the appropriate dose and the specific populations for its use. [1] The exorbitant growth and use of pharmaceuticals are managed in most of the nations by a regulatory system which sharply divides use into licensed and unlicensed categories. Drugs use confirming to the marketing label is known as labeled use. Off-label use is the use of pharmaceutical drugs for an unapproved indication, age group, dosage, or unapproved form of administration. [2]

Physicians are free to prescribe outside the licensing terms with certain caveats, but in doing so, their professional responsibility and liability increases outside the comfort level. Marketing license does not signify the best use of medicine in unlicensed indication so another terminology given by few physicians is “nearly label” for example use of antidepressant fluoxetine in the case of maintenance therapy of recurrent depression. [3]

Last decade has seen increased use of psychotropic medication. [4,5] Unlicensed use of drugs in psychiatry setting is very common feature in all sub specialties as compared to license drugs. [6-8] This use of off-label drugs was supported by strong scientific evidence in only 4% of cases. [9] Most common mode of off-label prescribing in Psychiatry Department is unapproved indication, dose, altered population. [10,11] Most commonly cited indication is depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic disorder, personality traits. [12] Prescribing of drugs in off label manner for nonapproved indication is mainly pharmaceutical companies driven as regulatory meshwork is more stringent and adding new indication will increase the patent value of newer congener drug. [13,14] Some psychiatrists think that clinical trials on psychiatric patients is a rarity and particularly in both the extreme of ages. They all also felt that off-label prescribing is needed as more than 80% of the psychiatric diagnosis by DSM-IV have no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medication. [15] Also for some drugs, randomized clinical trials data are not available for the use in resistant cases. But in last two decades, clinical trials have shoot up searching for new indications for already established psychiatric drugs, e.g., Duloxetine in neuropathic pain and gabapentin in anxiety and insomnia disorders. [16]

Atypical antipsychotics are the leading among psychiatric drugs which are always queued for off-label prescribing so their use should be weighed against their cost, regulatory status, and incomplete nature of available evidence. [12] There is a paucity of reports or studies in India. Hence, this study was planned to evaluate off label drug use in patients attending Outpatient Department of Psychiatry.

Materials and Methods

A prospective, cross-sectional study was carried out in Psychiatric Outpatient Department of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital over a period of 1-year from October 1, 2012 to September 30, 2013. Approval from Institutional Ethics committee was obtained. All the patients attending the Psychiatric Outpatient Department and those who agreed to give consent during this period were enrolled in the study after obtaining the consent of patient or patient’s guardian. Demographic data, complete clinical history, and complete prescription details were recorded in case record form. The prescription given to the patient including the drug prescribed, dose, frequency, and duration of the treatment was noted. British National Formulary (BNF)-2011 [17] was used as a reference source to identify off-label prescribing.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed by using SPSS version 21.0® IBM Corporation. Fischer’s exact test was used to determine the significant difference between labeled and off-labeled prescriptions for different variables. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine the association of offlabel prescribing with age, number of drugs. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Result

Demographic and morbidity pattern [Table 1]

| Variables | Number of patients | Number of label/off-label | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 137 | 29/108 | 1 |

| Female | 113 | 23/90 | |

| Age group | |||

| 0-20 | 19 | 0/19 | 1 |

| 21-40 | 105 | 31/74 | 0.0045 |

| 41-60 | 115 | 21/94 | 0.4348 |

| 61-80 | 11 | 0/11 | 1 |

| Morbidity | |||

| MDD | 101 | 23/78 | 0.5299 |

| No MDD | 149 | 29/120 | |

| Schizophrenia | 50 | 13/37 | 0.3321 |

| No schizophrenia | 200 | 39/161 | |

| Mania | 5 | 1/4 | 1 |

| No mania | 245 | 51/194 | |

| BPD | 67 | 10/57 | 0.2180 |

| No BPD | 183 | 42/141 | |

| OCD | 7 | 0/7 | 0.3504 |

| No OCD | 243 | 52/191 | |

| Co-morbidity | |||

| DM | 3 | 1/2 | 0.5048 |

| No DM | 247 | 51/196 | |

| HTN | 11 | 2/9 | 1 |

| No HTN | 239 | 50/189 | |

*Fischer’s exact test was used to calculate the difference between two groups. MDD: Major depressive disorder, BPD: Bipolar disorder, OCD: Obsessive compulsive disorder, DM: Diabetes mellitus, HTN: Hypertension

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of psychiatric psychiatrician patients based on off label (n=250)

A total of 250 patients were included in the study with a mean age of 40.36 ± 12.31 years (range 4–70 years). Male patient’s comprised 137 (54.8%) out of 250 patients. The most common diagnosis was major depressive disorder 101 (40.4%) followed by bipolar disorder 67 (26.8%), schizophrenia 50 (20%), obsessive compulsive disorder 7 (2.8%), and mania 5 (2%).

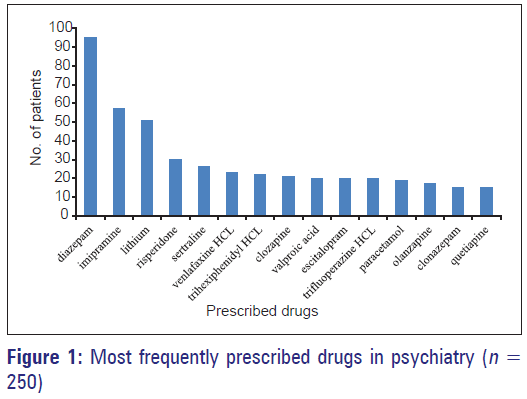

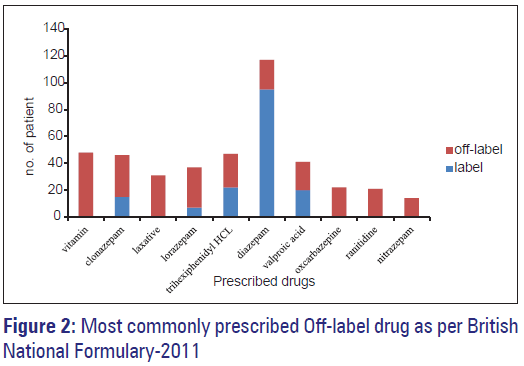

A total of 980 drugs were prescribed with mean number of drugs prescribed per patient 3.6 ± 1.42 (range 1–7). More than one psychotropic drug was used in 98% patients. Diazepam 117 (46.8%) was the most frequently prescribed drug followed by imipramine-57 (22.8%) and lithium 51 (20.4%) in 250 patients [Figures 1 and 2].

Off-label drug use

Of 980 drugs, 387 (39.5%) drugs were prescribed in off-label manner. Of 250 patients, 198 (79.2%) of patients received at least one off-label drug according to BNF. Number of patients who received more than one off-label drugs as per BNF was 109 (43.6%). The psychopharmacological drug most frequently prescribed in off-label manner was clonazepam 31 (12.4%), lorazepam 30 (12%), and trihexyphenidyl HCl 25 (10%) as shown in Table 2. Benzodiazepine was the most commonly prescribed group in off-label manner, which was seen in 106 (42.4%) patients. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics was seen in 14 (5.6%) patients only. Prevalence of off-label use of clonazepam, lorazepam, and trihexyphenidyl HCl was significantly higher than other off label drugs as per BNF (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Most common category for off-label prescription was inappropriate indication. Increase in the number of drugs in prescription increases the chances to receive more number of off-label drugs, there was positive and significant correlation between off-label prescribing and number of drugs (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.722, P ≤ 0.000 for BNF). Age and off-label prescribing was not positively or significantly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.086, P = 0.173 for BNF). Off-label prescribing was statistically significantly higher in 21–40 year age group, but no difference was seen in any co-morbid condition or in between any psychiatric disorder.

| Drug | ATC code | Number of patients* | Depression | Mania | OCD | Schizophrenia | Panic disorder | BPD | Delusion | PTSD | Epilepsy | Sedation |

| Clonazepam | N03AE01 | 31 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lorazepam | N05BA06 | 30 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trihexiphenidyl HCl | N04AA01 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diazepam | N05BA01 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sodium Valproate | N03AG01 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxcarbazepine | N03AF02 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nitrazepam | N05CD02 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Propranolol | C07AA05 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Risperidone | N05AX08 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Escitalopram | N06AB10 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zolpidem | N05CF02 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlordiazepoxide | N05BA02 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

*Patient can have more than one morbidity. OCD: Obsessive compulsive disorder, BPD: Bipolar disorder, PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder, ATC: Anatomical therapeutic chemical classification, BNF: British National Formulary

Table 2: Pattern of off-label prescribing in Psychiatry Outpatient Department as per BNF (n=250)

Discussion

The aim of our study was to analyze the proportion of off-label prescribing based on BNF in Psychiatric Outpatient Department. Mean age of patients in our study was low as compared with earlier Indian outpatient study which reported 33.9 years. This slight difference might be due to geographical variation in study settings. [18]

In our study, male:female ratio was 1.2:1 which was similar to other Indian studies study. [18,19] In our study most common diagnosis was mood disorders, that is, major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder which was similar to earlier Indian outpatient study which also reported the same. [18]

Mean number of drugs prescribed per patient in our study was 3.6 ± 1.42 which was higher as compared to previous Indian outpatient studies which reported 2.01 ± 1.03 this is due to difference in prescribing practices and different associated co-morbid conditions, [18] but this finding was in accordance to other Indian study focused on antidepressants drug utilization. [20]

In our study multivitamins, laxatives and ranitidine were most commonly prescribed drug groups which is in accordance with previous outpatient study from India, these drugs were given to counteract adverse effects associated with psychotropic drugs. [18] Diazepam was the most frequently prescribed drug followed by imipramine and lithium which was also evident in another local study which showed benzodiazepine was the most frequently prescribed drug. [19]

Prevalence of patients who received at least one off-label drug as per BNF was 79.2%, out of which who received more than one off-label drugs as per BNF was 109 (43.6%).

In our study, out of 980 drugs, 387 (39.5%) drugs were prescribed in off-label manner according to BNF which was comparable (i.e., 36.6%) to a previous inpatient foreign study done in UK using BNF. [21] And when compared to outpatient UK study, it was lower which reported 50% prescriptions as off-label. [22]

In our study, vitamin was the most common co-prescribed drug group. The drug most frequently prescribed in off-label manner was clonazepam 31 (12.4%), lorazepam 30 (12%), and trihexyphenidyl HCl 25 (10%) as per BNF.

Off-label prescribing pattern in our setup showed higher use of benzodiazepines as compared to atypical antipsychotics in other countries, this is due to difference in morbidity pattern as in our setup greater number of patients presented with depression and schizophrenia for which psychiatrist prescribed benzodiazepines for insomnia and attenuation of aggressive symptoms in schizophrenia patients, whereas in other setup anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dementia, severe geriatric agitation, eating disorders, and substance abuse were more prevalent. [23]

Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam were used in depression, mania, bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder in off label manner. Clonazepam is involved in the enhancement of anti-anxiety effects, anticonvulsant effects on subclinical epilepsy, augments in serotonin (monoamine synthesis) or diminish in serotonin receptor sensitivity mediated through the GABA system, and control in GABA activity. Low-dose, long-term treatment with clonazepam exhibits a prophylactic effect against recurrence of depression. Clonazepam is useful for treatment-resistant or protracted depression, as well as for acceleration of response to conventional antidepressants. [24] However, a systemic review of six randomized controlled clinical trial showed no added advantage of adding benzodiazepines to antidepressant drugs. [25,26]

Benzodiazepines were also used in schizophrenia as an off-label indication. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluated the efficacy of benzodiazepines. When BZDs added to antipsychotics, no evidence for added antipsychotic efficacy was seen. Therefore, benzodiazepines should be considered primarily for desired ultra-short-term sedation of acutely agitated patients but not for augmentation of antipsychotics in the medium- and longterm pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia and related disorders as seen in our study groups. [27]

Trihexiphenidyl HCL was used in bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia. The psychiatrists prescribe trihexyphenidyl as a prophylactic measure to decrease the incidence of extra-pyramidal reactions to anti-psychotic drug.

Newer drugs like oxcarbazepine were used for psychiatric conditions in off-label manner which was also seen in earlier studies. [28]

Most common category for off-label prescription was inappropriate indication which was similar to UK study. [8] We did not come across any studies from India related to off-label drug use in outpatient settings. Hence, we could not compare our results with equivalent Indian studies. There were a few limitations of our study; we included prescription from Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital so result may not accurately reflect practice in other settings. Study period can be extended but was adequate considering prospective design.

There is a need to raise awareness of off-label prescribing problem among psychiatricians so as to improve the prescribing of drugs. As FDA states, clinicians can prescribe off-label or unlicensed drugs provided they are aware about the benefits of such prescribing in certain special conditions. To ensure that patients are not exposed to unnecessary risks, controlled psychiatric clinical trials are required for drugs to determine the most appropriate indications for a particular drug.

For future studies, we can use DRUGDEX database which gives summaries of evidence based information on both on and off label indications, into three important evaluation dimensions (1) efficacy (in four categories: “Effective,” “evidence favors efficacy,” “evidence is inconclusive,” and “ineffective”), (2) strength of recommendation (in four categories: “Class I-recommended,” “Class IIa-recommended in most cases,” “Class IIb-recommended in some cases,” and “Class III-not recommended,” and (3) strength of evidence [in three graded categories: “A,” (good RCT evidence) “B,” (less consistent RCT evidence) and “C” (non-RCT forms of evidence)]. [29]

Conclusion

Off-label drug prescribing is prevalent in Psychiatric Outpatient Department in our setup. Among psychiatric patients use of off label drugs is common. Clonazepam, lorazepam, and trihexyphenidyl HCL were found to be the most frequently used drugs in off label manner. There is a need to raise awareness among psychiatrists and to encourage evidence-based off-label drug use. Moreover, use of various drug formularies also can improve the prescribing for psychiatric patients.

Source of Support

Nil

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Edersheim JG. Off-label Prescribing. Prescribing Times. Available from: Available from: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/labelprescribing# sthash.a9MTKKtC.dpuf. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 21].

- Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use – Rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1427-9.

- Healy D, Nutt D. Prescriptions, licence and evidence. Psychiatr Bull 1998;22:680-4.

- Murashev N. WARNING: ThinkTwice Before Filling Your Antidepressant Presciption; 2012. Available from: http://www.psychworld.com/thinkbefore- filling-antidepressent-prescription-2010-03. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 21].

- Ilyas S, Moncrieff J. Trends in prescriptions and costs of drugs for mental disorders in England, 1998-2010. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:393-8.

- Baldwin D, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2007;13:414-22.

- Haw C, Stubbs J. Benzodiazepines – A necessary evil? A survey of prescribing at a specialist UK psychiatric hospital. J Psychopharmacol 2007;21:645-9.

- Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:1175-81.

- Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1021-6.

- Douglas-Hall P, Fuller A, Gill-Banham S. An analysis of off-licence prescribing in psychiatric medicine. Pharm J 2001;267:890-1.

- Lowe-Ponsford F, Baldwin, D. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychol Bull 2000;24:415-7.

- Maher AR, Theodore G. Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics. J Manag Care Pharm 2012;18 5 Suppl B: S1-20.

- Kmietowicz Z. Eli Lilly pays record $1.4bn for promoting off-label use of olanzapine. BMJ 2009;338:b217.

- Tanne JH. AstraZeneca pays $520m fine for off label marketing. BMJ 2010;340:c2380.

- Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders The majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr 2009;2:29-36.

- Chouinard G. The search for new off-label indications for antidepressant, antianxiety, antipsychotic and anticonvulsant drugs. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2006;31:168-76.

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 61st ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press, Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2011.

- Thakkar KB, Jain MM, Billa G, Joshi A, Khobragade AA. A drug utilization study of psychotropic drugs prescribed in the Psychiatry Outpatient Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:2759-64.

- Piparva KG, Parmar DM, Singh AP, Gajera MV, Trivedi HR. Drug utilization study of psychotropic drugs in outdoor patients in a teaching hospital. Indian J Psychol Med 2011;33:54-8.

- Lahon K, Shetty H, Paramel A, Sharma G. A retrospective drug utilization study of antidepressants in the psychiatric unit of a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Diagn Res 2011;5:1069-75.

- Hodgson R, Belgamar R. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull 2006;30:55-7.

- Barbui C, Danese A, Guaiana G, Mapelli L, Miele L, Monzani E, et al. Prescribing second-generation antipsychotics and the evolving standard of care in Italy. Pharmacopsychiatry 2002;35:239-43.

- Maglione M, Maher AR, Hu J, Wang Z, Shanman R, Shekelle PG, et al. Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011 Sep. Report No.: 11-EHC087-EF.

- Morishita S. Clonazepam as a therapeutic adjunct to improve the management of depression: A brief review. Hum Psychopharmacol 2009;24:191-8.

- Barbui C, Cipriani A, Patel V, Ayuso-Mateos JL, van Ommeren M. Efficacy of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in minor depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:11-6.

- Ananthavarathan P. A Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of sodium valproate for “off-label” indications in mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:8e3.

- Dold M, Li C, Gillies D, Leucht S. Benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis and Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;23:1023-33.

- Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharma Stahlogy-prescribing Off-label in Psychopharmacology. Is it the Exception or the Rule. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- DRUGDEX® System. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Micromedex. Updated periodically. Available from: http://micromedex.com/. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 21].